- Joy Montgomery

- Nov 2, 2023

- 3 min read

Abstract

Economic growth during the postbellum period was particularly harsh in the South due to the “negative effects of the Civil War and slavery.” [1] According to Connolly, four factors led to the South reaching the turn of the century from the postbellum period as a low-skill, low-wage region: plantation legacy, education resistance, isolation of the labor market, and latecomer effects in reaching industrialization.[2] Economic development in Texas from 1860-1880 had a different set of circumstances and a growth in the sectors of the railroads and agriculture.[3] In Texas, hardships included the effects of the Civil War, ecological disasters (drought, floods, worms), and epidemics. In truth in Texas during Reconstruction, there was “much prosperity and significant economic development.”[4] Here is a comparison in Texas during the postbellum period in the railroad and agriculture sectors throughout the period from 1860-1980 to test the thesis that there was economic growth despite these hardships.

Methodology

Here is a regression model comparison of the railroad and agricultural industry throughout the period from 1860-1880, based on the work by Edmund Thornton Miller entitled “A Financial History of Texas” published by the University of Texas in 1916.[5]

Comparison

Herein is a comparison chart of the railroad and agriculture sectors throughout the period from 1860-1880 in Texas.

All industries here are on the rise from 1860 to 1870 to 1880. The only value that did not rise was the cash value of farms from 1860 to 1870. This trend is due to not only the Civil War, and loss of workers, but also due to weather conditions and epidemics in the years after the war. Between 1859 to 1869 in Texas, there were a series of droughts in the east, and floods and worms in central and southeast Texas.[6] Yellow Fever epidemics struck Texas rapidly in 1853, 1854, 1858, 1859, 1862, and 1867.[7]

In Texas agriculture from 1860 to 1870, the cash value of farms decreased but the percentage of improved land in farms and cotton production increased. In the Texas railroad industry from 1860 to 1870, the milage, manufacturing establishments, and manufacturing value of products increased. In Texas agriculture from 1870 to 1880, the cash value of farms, the percentage of improved land in farms, and livestock trade increased. In the Texas railroad industry from 1870 to 1880, the milage, manufacturing establishments, and manufacturing value of products increased.

Conclusion

Despite the economic hardship of the Civil War and the Reconstruction Era, weather incidents, and epidemics, Texas quickly recovered in both the agricultural and railroad sectors from 1860 to 1880.

[1]Larry Earl Adams, “Economic Development in Texas During Reconstruction, 1865-1875” (Denton, Texas, University of North Texas, 1980), 363, UNT Digital Library, https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc331534/.

[2]Michelle Connolly, “Human Capital and Growth in the Postbellum South: A Separate but Unequal Story,” The Journal of Economic History 64, no. 2 (2004): 367.

[3]Adams, “Economic Development in Texas During Reconstruction, 1865-1875,” iv.

[4]Adams, 201.

[5]Edmund Thornton Miller, A Financial History of Texas (University of Texas at Austin, 1916), https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/26568.

[6]Adams, “Economic Development in Texas During Reconstruction, 1865-1875,” 145–46.

[7]Penny Clark, “Yellow Fever,” in Handbook of Texas Online (Texas State Historical Association, April 2, 2020), https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/yellow-fever.

Bibliography

Adams, Larry Earl. “Economic Development in Texas During Reconstruction, 1865-1875.” University of North Texas, 1980. UNT Digital Library. https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc331534/.

Clark, Penny. “Yellow Fever.” In Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association, April 2, 2020. https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/yellow-fever.

Connolly, Michelle. “Human Capital and Growth in the Postbellum South: A Separate but Unequal Story.” The Journal of Economic History 64, no. 2 (2004): 363–99.

Miller, Edmund Thornton. A Financial History of Texas. University of Texas at Austin, 1916. https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/26568.

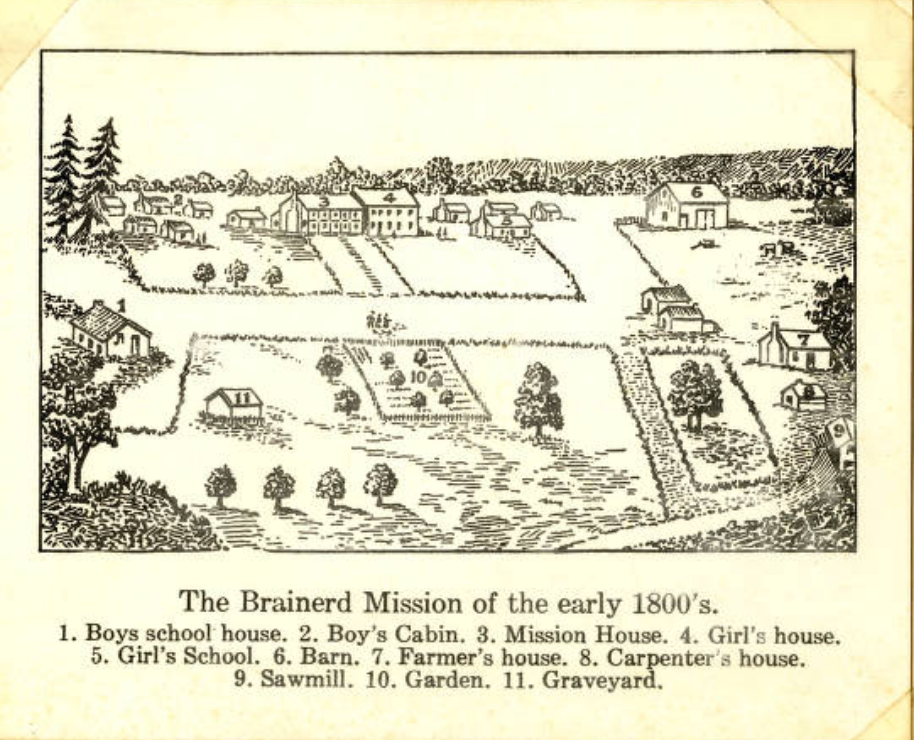

Research Topic

The research topic I have chosen for this class (HIUS 713) is the economic development of the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas from 1900-2023. I work at the Alabama-Coushatta Tribal Historical Preservation Office. They have undergone development in various industries from agriculture, lumber, tourism, and gaming. They have been through federal to state recognition, lost both, and gained back federal recognition. They have had to work for these recognitions and have traversed financial hardships in the interim periods. They are currently thriving and looking towards new developments in museum and tourism development. I hope to trace this timeline and the primary documents of development to show their perseverance through hardship, how they adapted, and how they have grown in recent years.